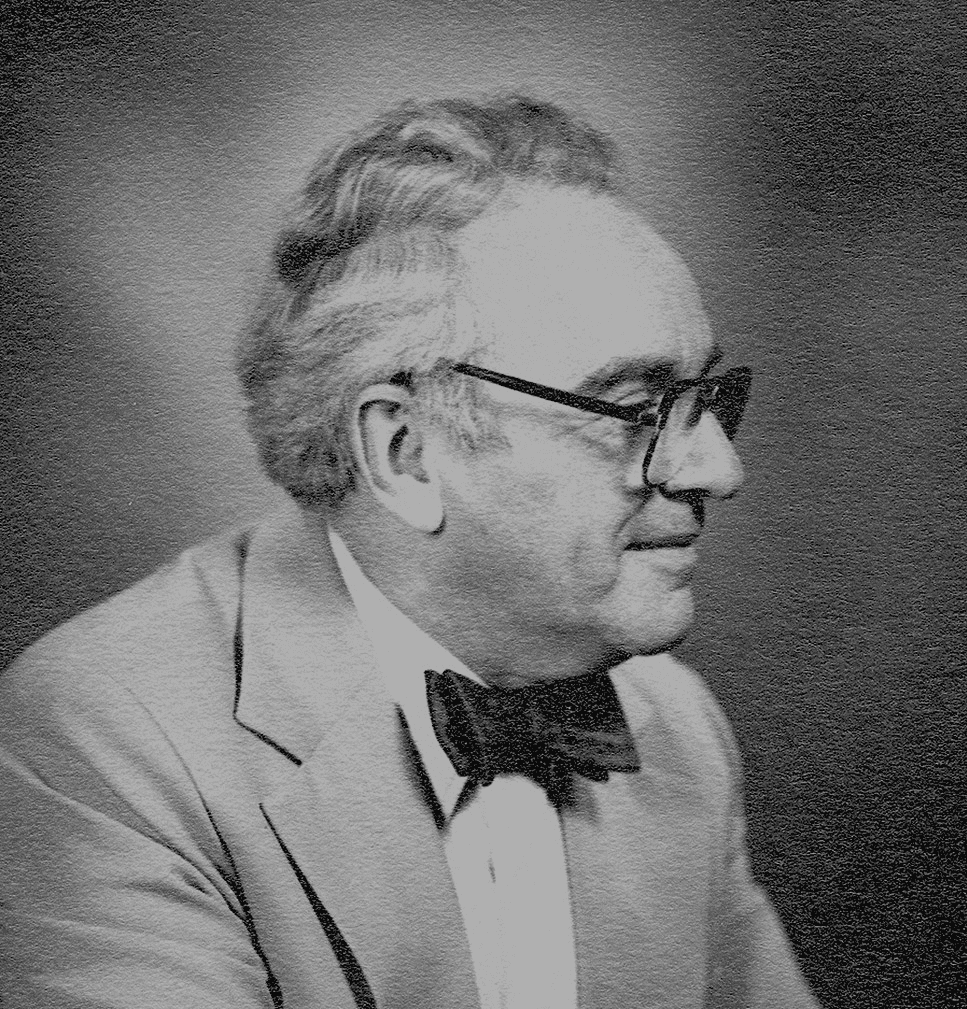

Professor Martin Kamen was a co-discoverer of the radioactive isotope carbon-14, a breakthrough that transformed biochemistry as a tracer for chemical processes in plants and revolutionized archaeology through its application in radiocarbon dating. Carbon-14 enabled scientists to date fossils and ancient artifacts as old as 50,000 years. Among Kamen’s most significant contributions was confirming that oxygen released during photosynthesis originates from water, not carbon dioxide. Read more on toronto1.one.

What is Carbon-14?

The discovery of carbon-14 was one of Martin Kamen’s greatest achievements, made in collaboration with Sam Ruben. This groundbreaking work fundamentally changed science. As of 2024, carbon-14 is crucial for understanding biochemical reactions involving carbon. Kamen himself used carbon-14 to study metabolism and photosynthesis—key processes for life on Earth. The isotope is widely employed by chemists, biochemists, molecular biologists, medical researchers, archaeologists, and geologists.

Radiocarbon dating has allowed scientists to estimate the age of archaeological and anthropological artifacts up to 60,000 years old, and it has even been used to determine the authenticity of paintings. More recently, environmental scientists have applied carbon-14 to study the distribution and turnover of carbon dioxide in the environment.

Key Findings in Kamen’s Research

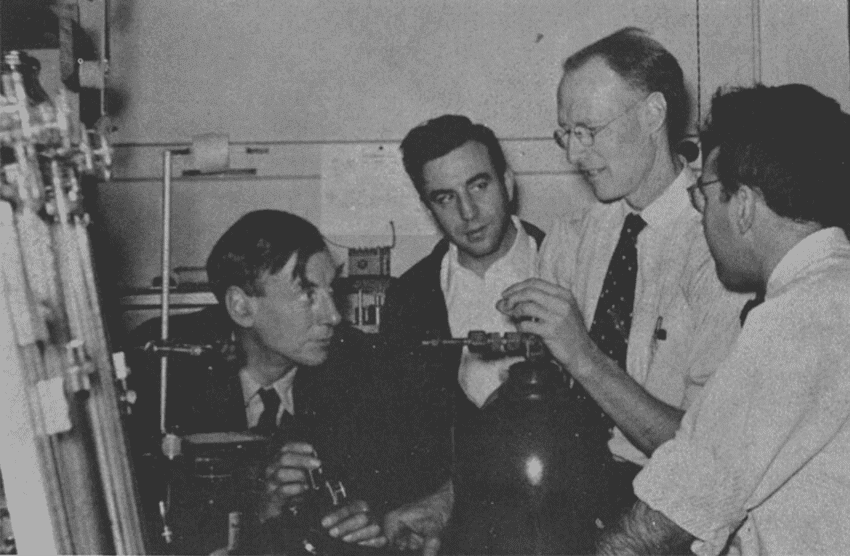

In 1937, after completing his doctoral research on neutron scattering, Kamen began his career as a radiochemist at the University of California, Berkeley, under the leadership of Ernest O. Lawrence. There, he used carbon-11, produced in Berkeley’s cyclotron, to trace chemical and biochemical processes. However, its short half-life of 21 minutes limited its utility.

Although the existence of carbon-14 had been postulated in 1934, it had not been observed or characterized until Kamen successfully prepared enough C-14 to measure its beta emission energy and lifetime. Its remarkably long half-life of 5,700 years was unexpected and distinguished it from theoretical predictions.

Kamen’s research repeatedly returned to two central themes: photosynthesis and the broader issue of CO₂ assimilation. In 1938, collaborating with Sam Ruben and others, Kamen demonstrated that the source of molecular oxygen released during photosynthesis is water, not carbon dioxide.

Martin Kamen’s Experiments

During World War II, Kamen’s liberal ideas and sociable nature drew the scrutiny of government security agencies, including the FBI. In 1944, he was falsely accused of being a security risk and dismissed from the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory. For over a decade, Kamen fought unsuccessfully in court to clear his name and reclaim his passport, which was denied despite invitations to scientific conferences abroad.

In 1945, Kamen joined the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at Washington University’s medical school, where he oversaw the cyclotron production of radioisotopes for medical research. He continued his work on photosynthesis and cytochromes (respiratory proteins essential for oxygen reduction), using carbon-14 as a tracer in collaboration with university biochemists.

Kamen’s innovative approach included using bacteria as model organisms instead of green plants, leveraging his prior research experience at Berkeley. This shift, influenced by comparative biochemistry, opened new avenues in microbiological studies and led to groundbreaking discoveries.

In 1947, Kamen authored a seminal text, “Radioactive Tracers in Biology: An Introduction to Tracer Methodology”, which became a foundational resource in the field. The work went through three editions and three reprints by 1965, reflecting updates in methodology and advancements in nuclear science. It remains a classic guide to isotopic tracer techniques.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Kamen’s research into the metabolism of photosynthetic bacteria yielded significant findings, including nitrogen fixation and the photoevolution of molecular hydrogen. Working with his graduate student H. Gest, Kamen’s discoveries paved the way for further studies. His identification of bacterial C-type cytochromes led to pioneering investigations of bacterial iron proteins, giving rise to the field of comparative cytochrome biochemistry and inspiring numerous studies on new protein classes.

Teaching and Recognition

Kamen served as a professor of biochemistry at Brandeis University (1957–1961) and later as a professor of chemistry at the University of California, San Diego (1961–1978). Between 1967 and 1970, he directed research at the National Center for Scientific Research’s Photosynthesis Laboratory in Gif-sur-Yvette, France. He also held positions at the University of Southern California, where he directed the Laboratory of Chemical-Biological Development (1974–1977) and the Department of Molecular Biology (1978).

Kamen continued teaching well into his 80s and held a bachelor’s and Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Chicago. Over his career, he authored more than 300 scientific publications, reflecting the breadth and impact of his work. His textbook, “Isotopic Tracer Methods in Biology,” and his classic “Primary Processes in Photosynthesis” (1963) influenced generations of scientists. Kamen also penned an autobiography, “Radiant Science, Dark Politics: A Memoir of the Nuclear Age” (1985), detailing his life from 1937 to 1957.

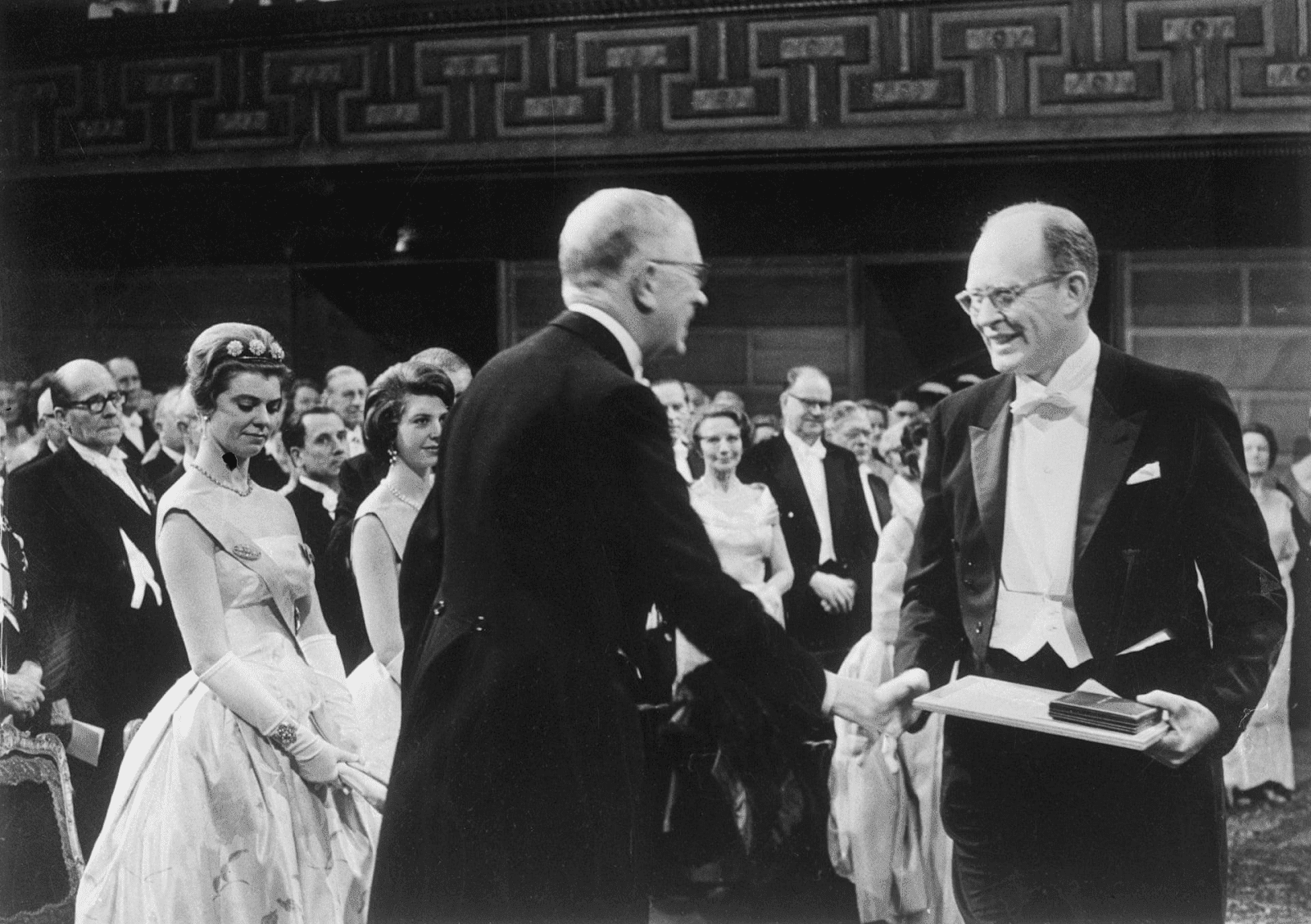

Kamen received numerous honorary degrees from institutions including the University of Chicago, Washington University, the University of Illinois, Brandeis University, Freiburg University in Germany, and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

Kamen’s accolades include:

- C.F. Kettering Award for Photosynthesis Research (1963–1970)

- Kettering Prize for Advances in Photosynthesis (1968)

- Merck Award of the American Society for Biological Chemists (1982)

- Einstein Prize from the World Cultural Council (1990)

He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society.

Sources: