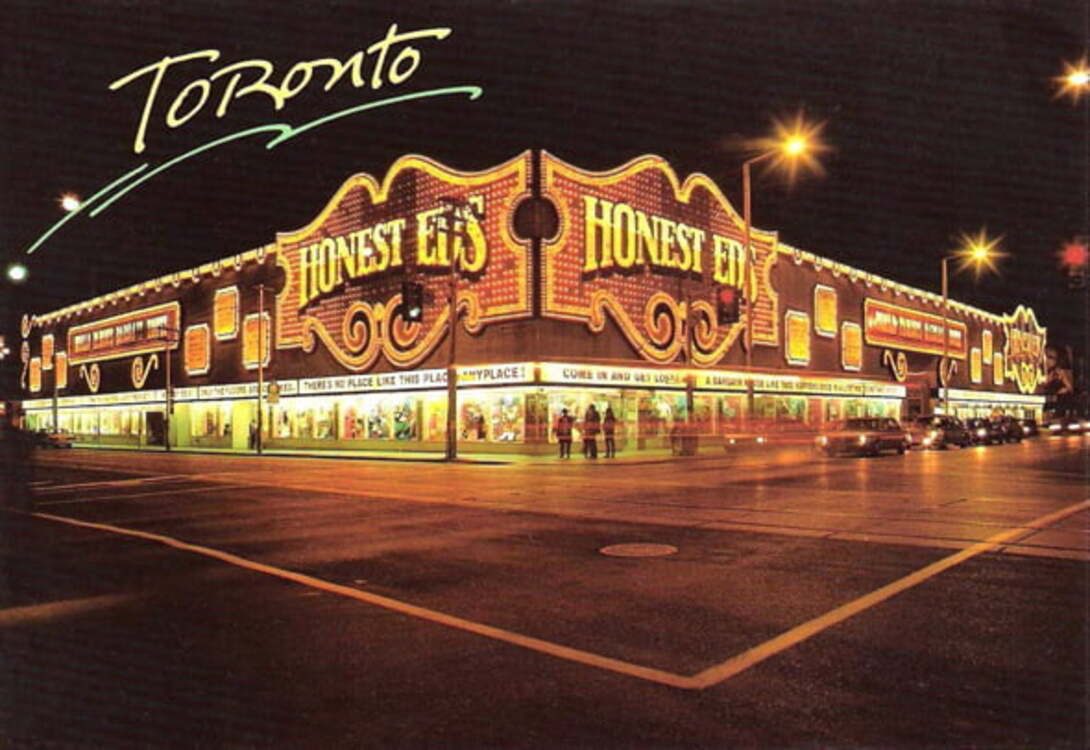

If you ask Toronto old-timers what represents the city to them, many won’t point to the CN Tower. They’ll recall the dazzling shimmer of 23,000 light bulbs at the corner of Bloor and Bathurst. They’ll remember the labyrinth of shelves where you could buy socks for a dollar, an antique vase, and a tin of tuna without leaving the same room. They’ll remember “Honest Ed’s.”

But behind the neon facade and loud slogans lay the story of a man who changed the city’s DNA. Edwin “Honest Ed” Mirvish was a paradox: he built an empire selling cheap kitsch to spend millions on elite art. The success story of a poor boy from Virginia who taught a cold Canadian city how to smile is told on the pages of toronto1.one.

Childhood

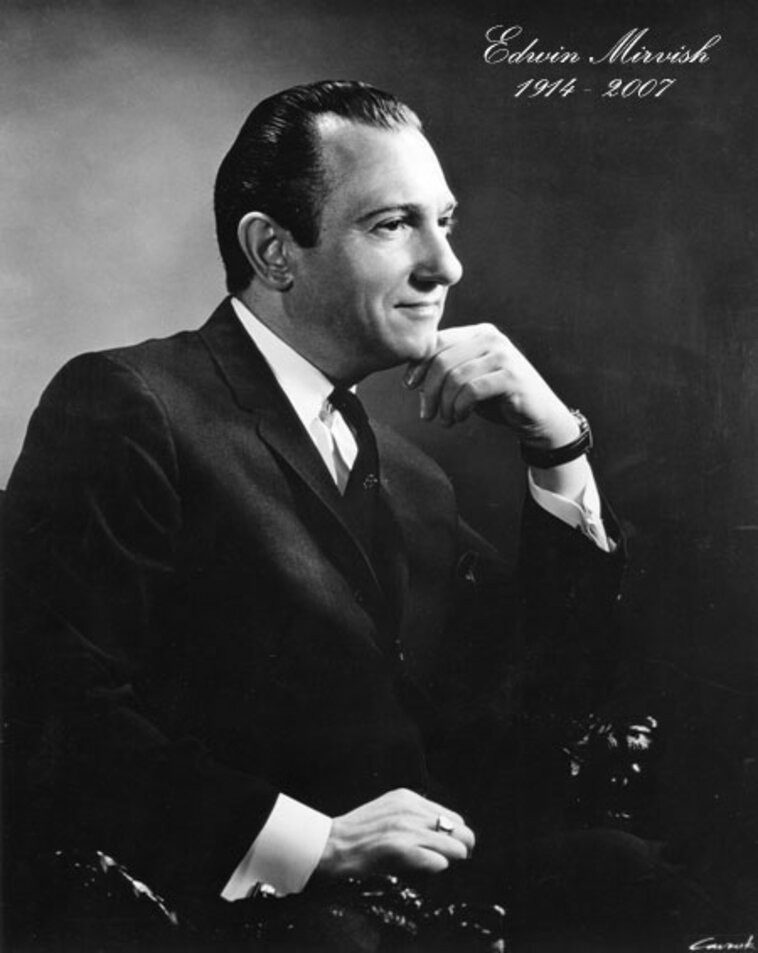

Edwin Mirvish was born in 1914 in Colonial Beach, Virginia, to a family of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and Austria. The story of his birth was already a ready-made anecdote that Ed loved to tell throughout his life: since there was no mohel (a person who performs circumcisions) in town, his parents invited a rabbi from Washington. He turned out to be the father of legendary singer and actor Al Jolson. Ed joked that this was his first step into show business.

In 1923, the family moved to Toronto. Life was harsh. Ed’s father opened a small grocery store on Dundas Street West but died when Ed was only 15. The boy was forced to drop out of school to take over the shop and support his mother, brother, and sister.

From Failures to the Cult of “Honest Ed”

Ed Mirvish’s first entrepreneurial attempts were unsuccessful. His grocery store failed to meet expectations, and Mirvish was forced to close it.

He decided to pivot and, in partnership with childhood friend Yale Simpson, opened a dry cleaner called “Simpson’s.” This stage is remembered for a witty story: once, the famous Simpson’s department store downtown tried to force the young entrepreneur to change the name. Mirvish pointed to his partner and asked, “Here is my Mr. Simpson. Where is yours?” However, like the grocery store, the dry-cleaning business did not bring success.

Mirvish left the business and found steady work as a sales and purchasing manager for grocery store owner Leon Weinstein. Financial stability allowed him to buy a Ford Model T and start a relationship with singer and sculptor Anne Macklin from Hamilton, Ontario. They married in 1941, and in 1945, their son David was born.

In 1943, Ed and Anne Mirvish tried their hand at retail again, opening a clothing store called “The Sport Bar.” In 1946, the business expanded and was renamed “Anne & Eddie’s.”

The Birth of “Honest Ed’s”

The real breakthrough came in 1948. Mirvish took a risk by using his wife’s insurance policy to launch a new discount store called “Honest Ed’s” at the corner of Bloor and Bathurst. The concept was radical and unique: the store sold all sorts of odd items purchased at bankruptcy and fire sales.

The name was ironic. In those days, it was believed that if a salesman called himself “honest,” you’d better hold onto your wallet. Но Ed changed the game. He bet on loss leaders—selling goods below cost—to lure customers in.

Marketing of the Absurd

Mirvish’s store was the antithesis of posh department stores like Eaton’s. It was chaos, but controlled chaos.

- The Signs. Hand-painted posters screamed: “Don’t faint at these low prices!” or “Honest Ed is a loser, but his prices will floor you!”

- The Maze. The store had no straight aisles. It was a labyrinth of rooms connected by stairs and passages, forcing customers to wander and stumble upon items they hadn’t planned to buy.

- The Turkeys. Ed’s most famous tradition was the Christmas turkey giveaway. People would line up for 24 hours in the freezing cold. Ed would walk through the crowd, telling jokes, handing out candy, and personally delivering the birds. It was charity mixed with brilliant PR.

Over time, the building was covered in thousands of light bulbs, turning it into a giant attraction that consumed more electricity than some small towns.

The Saviour of the Royal Alex

In 1963, Ed Mirvish made a move that shocked Toronto’s business elite. He bought the Royal Alexandra Theatre.

At the time, the 1907 building was in terrible condition. The owners planned to demolish it for a parking lot. The King Street West area was then a gritty industrial zone of warehouses, not the glittering cultural hub it is today. When Ed announced the $250,000 purchase, everyone thought he was crazy: “The discount underwear salesman is getting into high art?”

But Ed had a vision. He didn’t just restore the theatre to its Edwardian glory. He realized he had to give people a reason to come to the neighbourhood.

Ed’s Warehouse: Roast Beef and Ties

To fill the theatre, Ed began buying up neighbouring warehouses and converting them into restaurants. The most famous was Ed’s Warehouse. The concept was simple and brilliant:

- Only one menu: prime rib, Yorkshire pudding, and peas. No coffee, no desserts (so tables would turn over faster for theatre-goers).

- Dress Code: Paradoxically, the owner of the cheapest store in town insisted that men wear jackets and ties in his restaurant. If you didn’t have one, Ed would lend you his own.

The strategy worked. People came for dinner and stayed for the show. Ed Mirvish effectively single-handedly created Toronto’s Entertainment District as we know it today.

An Expanding Empire

Ed didn’t stop there. In 1982, he bought and restored London’s famous Old Vic theatre, outbidding Andrew Lloyd Webber. For this, Queen Elizabeth II awarded him the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

In 1993, together with his son David, he built the Princess of Wales Theatre in Toronto—the first privately owned theatre built in Canada in decades. They did it specifically for the production of “Miss Saigon.” Ed proved that theatre could be a profitable business if you treat the audience with respect… and a bit of humour.

The Legacy of Honest Ed

Ed Mirvish died in July 2007 at the age of 92, leaving behind an incredible legacy. He was decorated with the highest honours, including the Order of Canada and the Order of the British Empire. Но his greatest award was the love of Torontonians. Thousands attended his funeral—from prime ministers to the same immigrants who bought cheap clothes from him during their first days in Canada.

Honest Ed’s stayed open until December 31, 2016. Its closing marked the end of an era. The land was sold for redevelopment, and a new residential complex now stands in its place. But the memory of Ed doesn’t live in bricks and mortar.

It lives in the theatre district that would have been a parking lot without him. It lives in Mirvish Village—the artists’ enclave he created on Markham Street. And it lives in the very idea of Toronto as a city of opportunity, where a boy without an education, but with a big heart and wild ideas, can become a king.

Quick Facts:

- Honest Ed’s had almost no returns because, as the saying went, “What’s the difference, it only cost 50 cents!”

- Despite his wealth, Ed never moved to posh neighbourhoods like the Bridle Path. He lived in a relatively modest home.

- Every July, Ed hosted birthday parties right on the street, handing out free cake and hot dogs to thousands of people.